Menu: Site Background | 3D Site Plan | Dive Video | Site Detail | Final Voyage

In 1707 Sir Cloudesley Shovell’s fleet was in the Mediterranean off Toulon. As winter approached, Sir Cloudesley left a squadron in the Mediterranean and set off for England with the rest of his fleet. This fleet consisted of 21. Having miscalculated their position, the fleet ran into the Western Rocks off Scilly during the evening of 22nd October 1707. (The date on Navy ships of this period changed at noon, thus on ship the afternoon has a later date than the afternoon on land). Three ships, Eagle, Romney and Sir Cloudesley’s flagship Association, were lost with only a single survivor (from the Romney) between them. The fireship Phoenix struck a rock and was eventually beached at New Grimsby (Tresco), where she remained for three and a half months undergoing. Another fireship ‒ the Firebrand ‒ also struck the rocks but managed to get off again. Leaking badly, she made for the beacon of St Agnes lighthouse, but foundered in Smith Sound close to the island of St Agnes. Of Firebrand’s crew of 48 only 18 ‒ including Captain Percy ‒ managed to reach the safety of St Agnes.

What went Wrong?

Navigation at sea at this time was not a precise science. This is amply illustrated by the dispatch of the frigate Tartar from Plymouth to cruise up and down looking for Sir Cloudesley’s fleet in order to ‘give him advice how the land bears from him’. To enable them to do this, they were instructed to ‘make the land every day’.

In 1960 Commander May wrote a detailed analysis of the surviving logbooks from the fleet. He concluded that the navigational errors were due to a number of different causes, including currents, compasses, and errors in the published navigation tables as well as inability to accurately determine longitude:

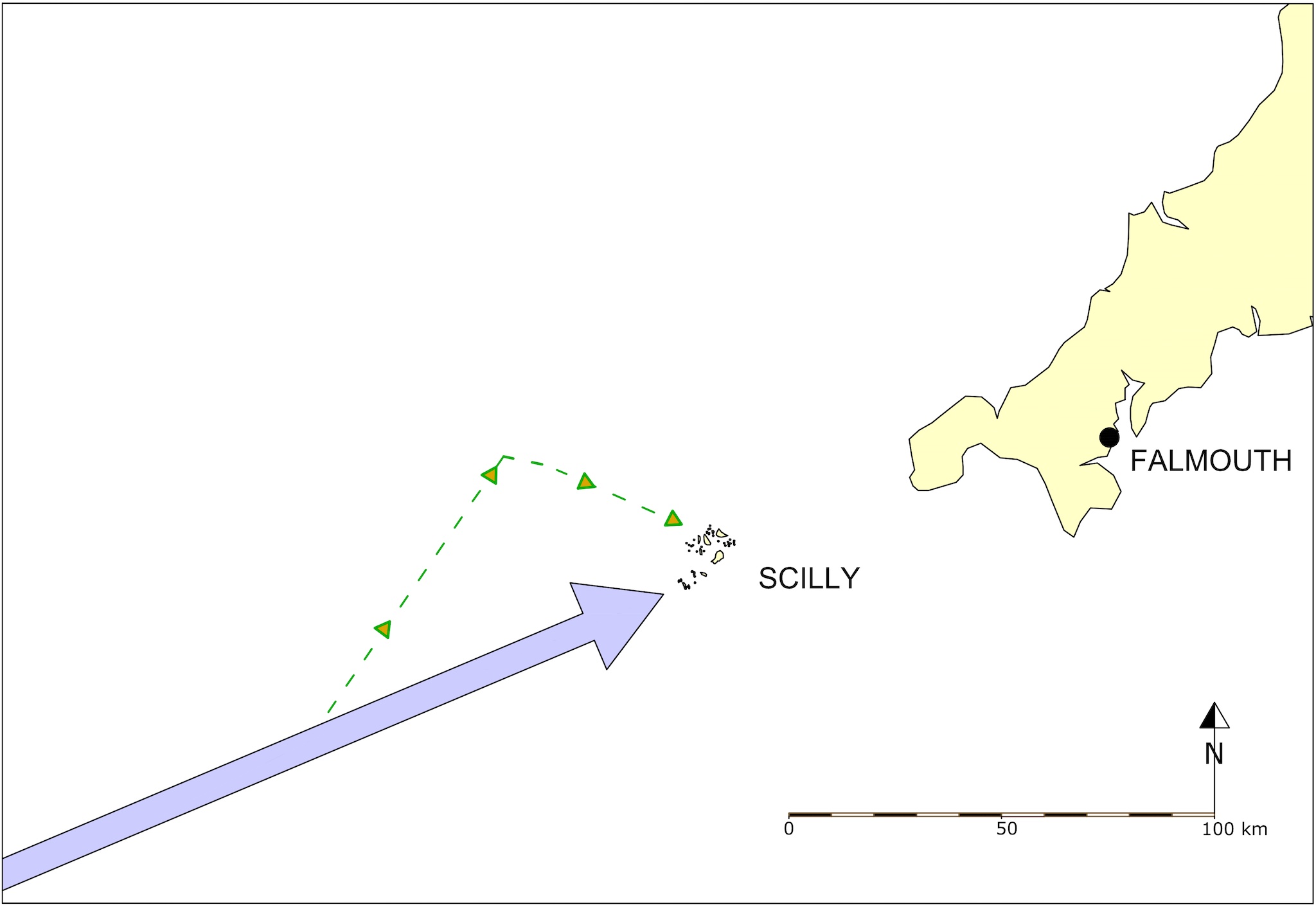

A good indication of where the fleet thought they were is given by the illustration of the three ships detached from the fleet to go to Falmouth for convoy duties. When they left the fleet at 11 am on the morning of the disaster, the fleet were sailing ENE towards their encounter with the rocks of Scilly that evening. But they thought they were clear of Scilly with the Channel open before them. The three detached vessels, Lenox, Valeur and Phoenix set off on a course of NEbyN (about 34⁰ east of north). This course to Falmouth only makes sense if they thought they were in the Channel and east of Land’s End. In the event they were west of Scilly so did not encounter the coast of Cornwall as expected and turned eastward, only to run into the Islands where the Phoenix was badly damaged on the rocks off Samson and was forced to run aground on the sand flats near Tresco. This amply demonstrates that the error the fleet made, and which ultimately cost so many lives, was in calculation of their longitude (location east to west).

The Longitude Prize

At the time of the disaster there was no easy way of determining a ship’s longitude, which until the 18th century mariners gauged by means of ‘dead reckoning’.

Dead reckoning – This is a plot of the ship’s position on a chart, and was constructed from the distance travelled and the course steered. The distance was determined by the use of a log line. This was a piece of wood attached to a line marked out in knots and fathoms; it was cast into the sea and allowed to run out for a set time (usually 28 seconds – measured with a sand glass). The course and speed were marked onto the log board every ‘bell’ (30 minutes). The master plotted this onto the chart at the end of every watch. The system was prone to many errors, and as each plot began where the last one ended the errors quickly accumulated.

Latitude (position north to south) – This could be determined with reasonable accuracy by measuring the maximum height of the sun or the pole star above the horizon. This angle could be used to calculate latitude. At the end of the seventeenth century this measurement would usually be made using a back staff.

Longitude (position east to west) – This can easily be calculated by comparing local noon (highest rise of the sun) with the time of noon at Greenwich (zero degrees longitude). Every four minutes of difference represents one degree of longitude. Unfortunately this requires an accurate timepiece (chronometer) which was not available to mariners in 1707.

This could have disastrous consequences and on the night of 22 October 1707, Sir Cloudesley Shovel had mistaken his longitude and was heading for the Western Rocks. The ensuing catastrophic loss of four warships along with the Rear Admiral of England and some 1340 men brought the question of longitude to the forefront of national affairs and precipitated the Longitude Act of 1714 in which Parliament promised a prize of £20,000 for a solution to the longitude problem ‒ the Longitude Prize ‒ which John Harrison eventually won with his chronometer c 1736.

Rediscovery

The archaeologist John Dunbar led a diving expedition to Scilly in 1956; this may have been the first use of Self-contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus (SCUBA) equipment in the islands. He was looking for the historic wrecks of Colossus and Association and found no trace of either although he was aware that Association was wrecked on the outer Gilstone (Dunbar 1958).

The wreck of the Association was rediscovered on 4 July 1967 by Naval Air Command divers. It was not a chance discovery; they had been searching for the wreck since their first expedition to Scilly in 1964. That year they recovered iron cannon from the inner Gilstone which led to the following by-line in the local paper: ‘Relic of historic wreck found by divers off Scillies – cannon from HMS Association’ (Cornishman, 2 July 1969). They soon realised that this was not the site of Association; in fact the St Mary’s lifeboat coxwain, Matt Lethbridge, informed them that the outer Gilstone was, by long standing Scillonian tradition, the site of the wreck (Richard Larn, pers comm).

The Association anchors

In August 1967 the Fleet Air Arm divers raised one of the large bower anchors and placed it in shallow water ‘south-east of Nut Rock’ for safe keeping. The anchor was declared to the Receiver of Wreck on 25 August 1967, donated to the Islands council and accepted by them at their October 1967 meeting (Cornishman, 5 October 1967).

The anchor, however, remained on the seabed until 2013 when it was rediscovered by local divers, raised and placed in a field on St Mary’s. The divers thought it might be one of the missing anchors from HMS Colossus, but it was soon realised to be the anchor raised by the Fleet Air Arm divers in 1967. Is this the first time the same object has been declared to the Receiver of Wreck twice? In 1968 the Morris team also raised a large bower anchor from the site; this anchor is now attached to the gable of the house which housed Morris’ first nautical museum in Chapel Street, Penzance .

Sir Cloudesley Shovell’s homeward bound fleet, October 1707

| Ship (guns) | Class | Crew* | Captain | Comments |

| Royal Anne (100) | First Rate | 750 | William Passenger | Flagship of George Byng |

| St George (96) | Second Rate | 680 | Lord Dursley | |

| Association (90) | Second Rate | 680 | Samuel Whitaker | Flagship of Sir Cloudesley Shovell |

| Somerset (80) | Third Rate | 476 | John Price | |

| Torbay (80) | Third Rate | 476-520 | William Faulkner | Flagship of Sir John Norris |

| Eagle (70) | Third Rate | 460 | Robert Hancock | |

| Lenox (70) | Third Rate | 460 | Sir William Jumper | |

| Orford (70) | Third Rate | 460 | Charles Cornwall | |

| Swiftsure (70) | Third Rate | 440 | Richard Griffith | |

| Monmouth (66) | Third Rate | 440 | John Baker | |

| Panther (54) | Fourth Rate | 280 | Henry Hobart | |

| Romney (54) | Fourth Rate | 280 | William Coney | |

| Rye (32) | Fifth Rate | 145 | Edward Vernon | |

| Valeur (24) | Sixth Rate | 110 | Robert Johnson | Ex French warship La Valeur |

| Cruizer (24) | Sixth Rate | 115 | John Shales | Ex French warship Le Meric |

| Weasel (10) | Sloop | 80 | James Gunman | |

| Isabella (10) | Yacht | 30 | Finch Reddall | |

| Vulcan (8) | Fireship | 45 | William Ockman | |

| Firebrand (8) | Fireship | 45 | Francis Percy | |

| Griffin (8) | Fireship | 45 | William Houlding | |

| Phoenix (8) | Fireship | 45 | Michael Sansom | Damaged but not lost |