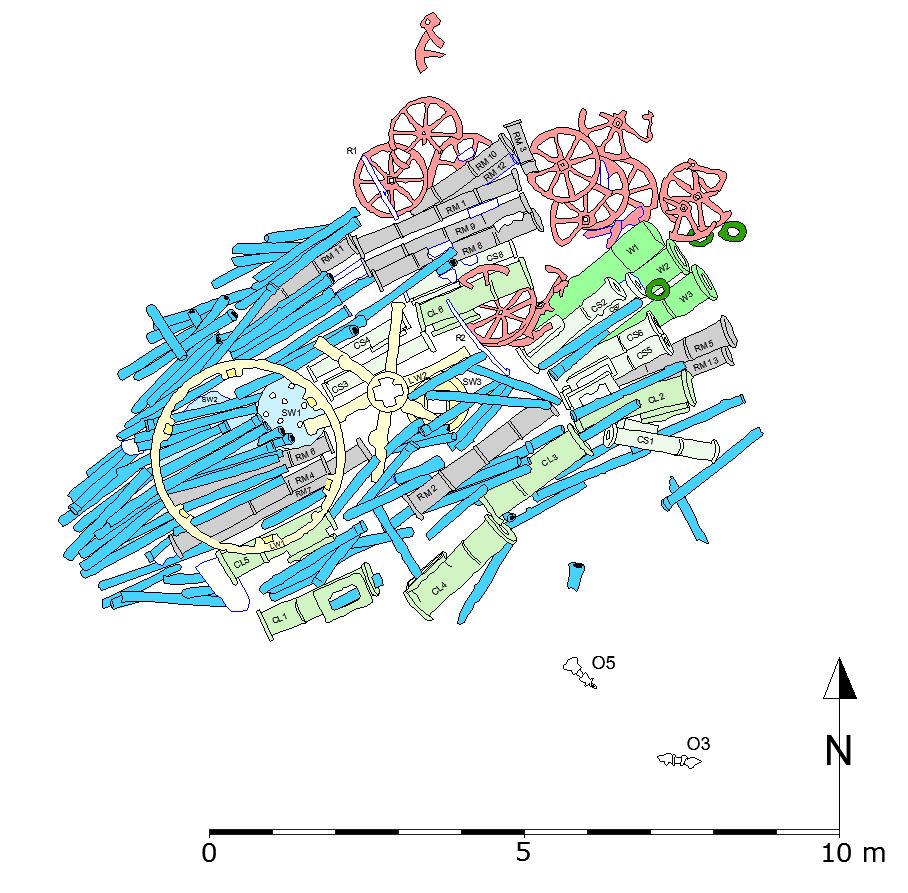

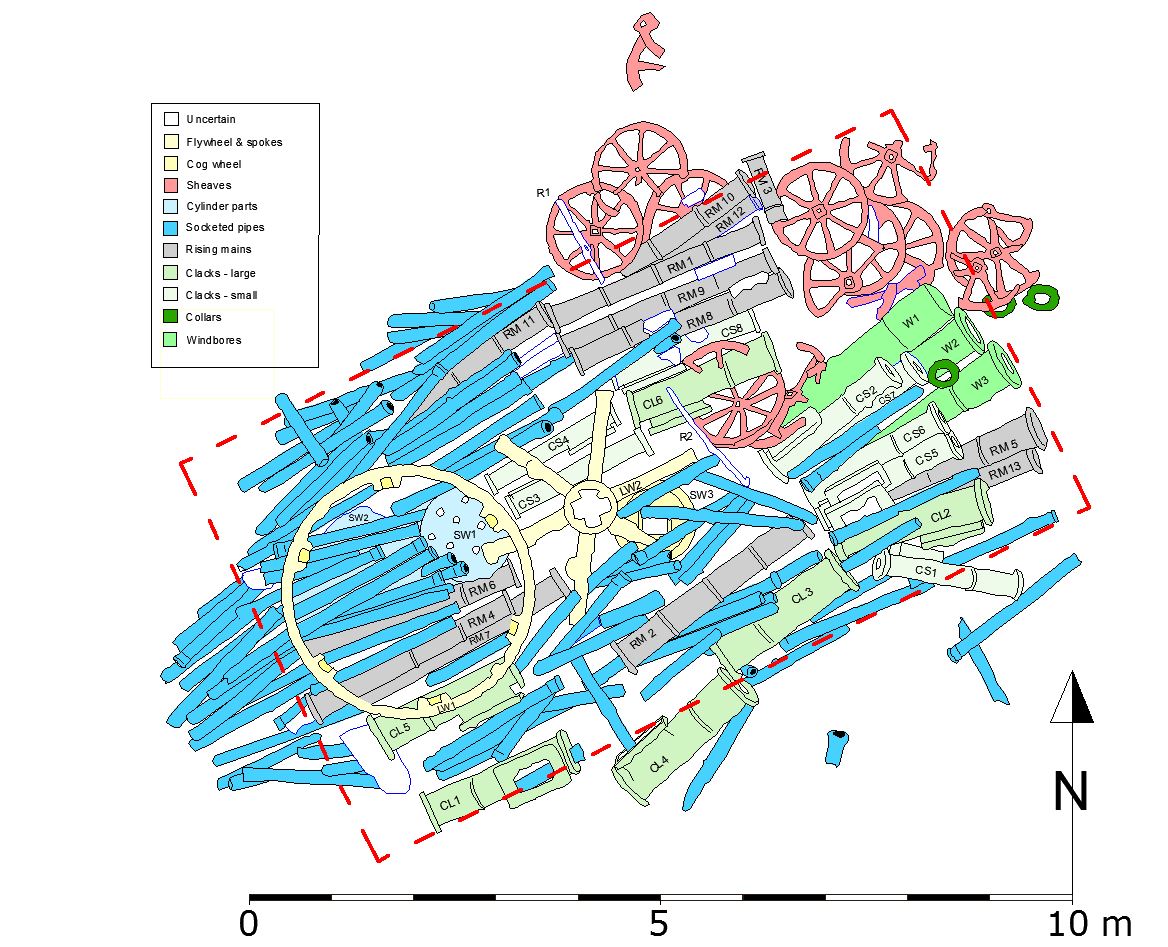

Wheel Wreck: Intro | Cargo mound | Iron cylinder |Remains of the vessel | 3D site plan | Dive video

We do not know the name or the precise date of the vessel carrying the ‘Wheel Wreck’ cargo. The finds recovered from around the cargo suggest a date of 1780-1820. Very few objects originating from the vessel (rather than personal items or the cargo) have been located: three lead scupper pipes, eight wooden block-sheaves with copper-alloy coaks, and two complex iron objects which were possibly windlasses. In addition some lead sheathing probably also originated from the vessel. The distribution of these objects is similar to that of the pottery and glass which has been recovered.

The paucity of remains from the vessel itself is puzzling; at the very least the anchors should be evident. Even a simple wooden vessel requires iron or copper fastenings to hold the hull together –no hull fastenings have been located on this site. The lack of ironwork associated with the masts and rigging is perhaps more easily explained as these could easily have drifted away or been salvaged shortly after the loss of the vessel. However, the nature of the seabed around the cargo mound (large, tightly packed granite boulders) makes locating small objects difficult.

The three lead scuppers found would have been firmly attached to the hull timbers until the timber rotted away – perhaps indicating that parts of the hull remained on site until it decayed. The decay of the timber would have been fairly rapid given the rocky nature of the seabed, which would have precluded burial and preservation of timbers within anaerobic sediments. The only timber seen on this site is the badly gribbled and eroded remains of lignum vitae sheaves recovered with the copper-alloy coaks. The lead scuppers appear to be deck scuppers and their relatively small diameter (0.06m) and short length (0.33m) would seem to indicate a fairly small vessel.

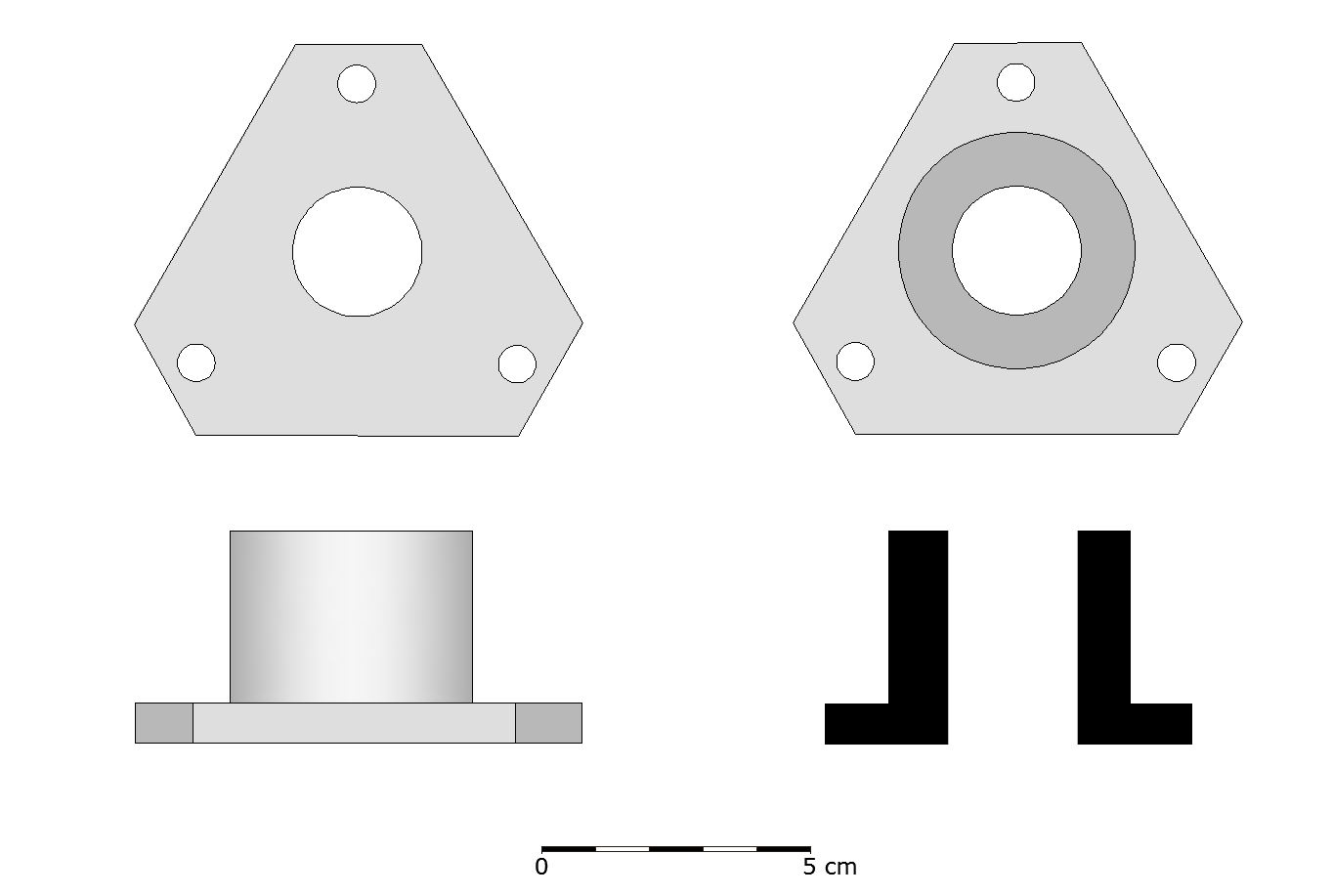

The copper alloy sheave coaks are of a distinctive triangular shape. They would have acted as bearings for the wooden pulley sheaves – which would have been part of the running rigging of the vessel. The coaks are of similar size and shape. Interestingly, although superficially the same, the dimensions vary significantly, suggesting that they were handmade or finished.

Similar coaks have been found on the wreck of the General Carleton, built at Whitby in 1777 and wrecked off the Polish coast in 1785.

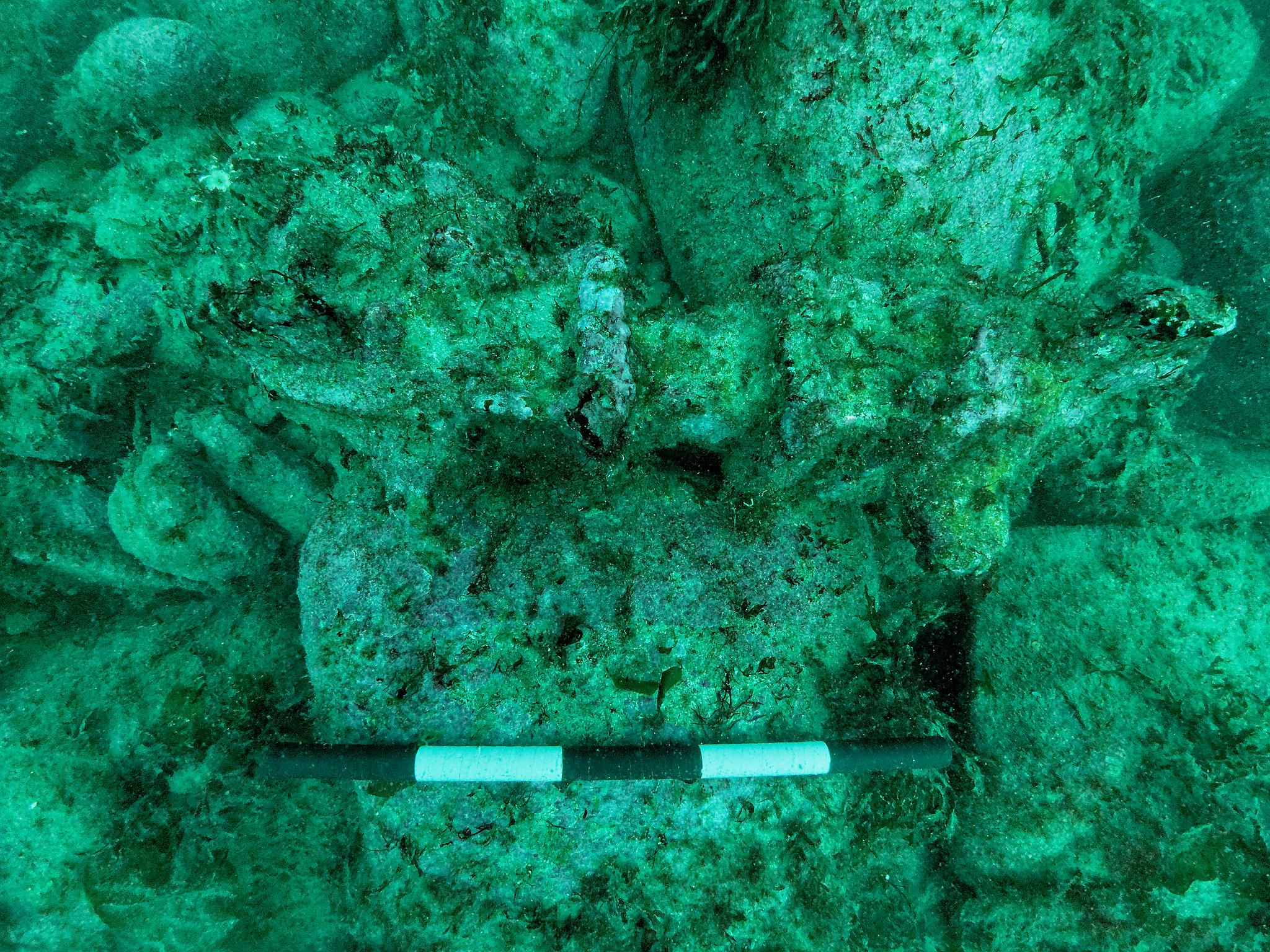

Other items found which may be attributable to the vessel are the two complex iron objects (O3 & O5) which were found on the seabed to the south of the cargo mound (see figs 40 & 48).

The sheet lead (F28) – which has nail holes along its edges – is probably lead sheathing, which was probably part of the vessel. Three similar lengths of lead sheathing were observed at the western end of the cargo mound. These were of similar width and thickness to (F28) but were longer (approximately 0.6m long).

Scale = 0.10m

The size of the vessel

The cargo mound presents as a coherent, orderly pile of iron objects some 12m by 7m. However, in several places around the edges it is clear that some collapse has occurred, presumably as the wooden sides of the hold decayed. A conjectural reconstruction of the hold outline is presented above – this results in a hold which is 5.4m (17.6 ft) wide and 9.65m (31.7 ft) long

If we take this estimate of the hold dimensions – especially the width of the hold, which has to be less than the beam of the ship – we can compare the width with the beam of ships known to be engaged in the transport of this type of cargo and arrive at an estimate of the size of the vessel concerned. It would appear that our hold width of 17.6ft could be accommodated by a vessel of 70 – 100 tons. Two examples from the Harveys fleet are Fame (1814) brigantine, 106 tons, 63ft long and 20ft wide and Park (1829) snow, 117 tons, 66ft long , 23ft wide. This probably gives us a rough idea of the size of the vessel which we are dealing with here. In any case, we are almost certainly looking for a vessel with a minimum beam of 18 feet.